COMBAT KARATE: a different approach for fighting

Before addressing the subject of “Combat Karate” in its various and articulated aspects, it is

necessary to clarify “what Combat Karate is not.” First of all, Combat Karate is not a new style of

karate but it is a term basically used to describe a different kind of “karate approach for fighting”,

an approach that requires different forms of training and that develops new and effective

techniques, albeit sometimes performed in ways that do not properly fit those criteria imposed by

traditional karate. There is still no official definition of it, perhaps because its exact position

between tradition and innovation has yet to be established, and perhaps for that reason there are

several definitions to attempt a categorization. The simplest one is clearly “karate for combatting”

...but is there any karate style that is not “for combatting” ???

As a preliminary point, it must be emphasised that “Combat Karate” is not “Karate Combat”.

Karate Combat (KC) indeed is a famous commercial brand, one brand among many (K1, UFC...),

which promotes professional karate fights in “full contact fighting” (i.e. without the control of

blows), without distinction of styles of origin or schools. In recent years, in fact, the world of

combat sports, and Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) in particular, have promoted, through numerous

associations, federations and sports organisations, various types of championships, competitions

and tournaments at a professional level (with different criteria for awarding victory, scoring

schemes, competition regulations, techniques allowed or not, the possibility of wearing protections

or gloves....), causing the proliferation of numerous television entertainment “formats” that

capitalise even several millions of dollars per year on the Stock Market.

The development of full-contact fighting in the “combat sports” has long since taken place within a

fair number of karate styles (e.g. Kyokushin, Shidokan, Shindenkai, Seidokaikan, Ashihara,

Enshin...) as well as relatively more recent karate styles that also involve the use of throwing

techniques and grappling techniques (Ashigaru-Ryu Karate, Seireikan Karate, Kudo/Karate Daido

Juku/Kakuto Karate, Nihon Zendokai.... ) leading karate, in general terms, to implement innovative

modifications both in terms of training development and in terms of enriching its technical wealth

of knowledge with the acquisition of techniques from other combat disciplines (e.g. the “fukubi

tomeru geri” - kick to the abdomen, or hips, to block the opponents forward movement using a

kick similar to a tiip (kick) used in the Thai discipline of Muai Lert Rit).

Obviously, the technical validity of these forms of fighting, beyond the constraints of sporting

application, has allowed the various karateka to successfully face even those fighters who employ

numerous techniques from different disciplines, including that mixture of martial arts known in

Japan as “Sogo Kakutogi” (“Composite Combat” or “Composite Fighting”). Leaving aside now the

purely sporting aspects, the fact remains that the so-called “traditional” karate has itself also been

subject to a certain amount of innovations both in terms of training and in terms of interpretation of

techniques, emphasizing points of solidity from tradition while at the same time introducing

innovative concepts in both techniques and training methods. Certainly a number of karate Masters

have had to smooth over, even with themselves, points of disagreement in order to harmonize the

“old” with the “new” in order to evolve, as it happens in any art or discipline whose intent is to

progress towards further and significant developments.

But let us return to Combat Karate by identifying what exactly it means by observing three aspects:

the training, how the techniques are carried out and therefore the resultant combat tactics. There are

clearly links with various styles and schools of karate, but it will be the personal experience of the

individual reader to identify and decide affinities and differences.

As a preliminary, it is necessary to deal with a much-debated topic, namely that of “kimè” and what

it entails in the “power generation of the strike”. The word kimè is one of those words that can have

many meanings, although sometimes only a few are considered enough to provide a sufficiently

comprehensive explanation. In fact, the word kimè is translated with a dozen different meanings,

but the most common ones are; “intention”, “decision”, “contraction”, “focal point of

concentration”, “impact”, “power”. Actually, kimé is a concept of both Chinese (fa jing) and

Okinawese (chinkuchi / muchimi) derivation and now it is found almost exclusively in Japanese

martial arts. Leaving aside the complex oriental theories on the creation and transfer of energy,

however, it is not easy to univocally define kimè and it is simpler to explain its meaning: kimè

represents a point of maximum concentration in which the mind, body and spirit combine together

to instantaneously direct the maximum power of a strike onto a target by using ones own inner

energy (ki) rising from the abdominal area (hara/tanden).

This is an effective and instantaneous transfer of kinetic energy from ones body to the target which

is achieved through a very rapid contraction and subsequent immediate relaxation of muscles,

tendons and nerves, often exploiting the rotation or movement of the hips (koshino kaiten). The

aesthetic result is that rapid “robotic-mechanical” movement with which a blow is instantly

blocked, as is particularly highlighted in the practice of kata or kihon. That “robotic” movement

allows a greater transfer of destructive energy onto the target, guaranteeing a better balance of the

body and safeguarding the joints of the arms or legs from possible injuries caused by those violent

and immediate hyperextension of the muscles, tendons and nerves. This concept is extremely

divisive among martial arts practitioners as many combat disciplines, which do not use kimé, but

develop nevertheless extremely powerful strikes by delivering the same strikes “in a lunge way”,

without having to “block” a strike (theoretically “before the target”, or “on the target” or “a little

beyond the target”), through that contraction required by traditional karate to achieve the famous

“good kimé”. For the traditional approach indeed (initially based on “no-sporting aims”) not having

a good kimé means “not having a technique to be considered powerful and effective”. Certainly

nobody would dream of stopping a hammer blow while hammering nails or stopping an axe blow

while chopping wood to make the blow more powerful, but those are clearly different concepts of

the application of force and power. Obviously over time many arguments have been made, both for

and against kimé, but perhaps the best way, as the Okinawan Grandmaster Shoshin Nagamine (of

the Matsubayashi Shorin-Ryu Karate / founder of the martial art of Taido) suggested, to overcome

this thorny argument lies in practising karate considering kimè as “a fundamental personal

experience” or “an added value” to achieve a karate of excellence, without ever precluding new

“adaptations” of enrichment, development and improvement by “exploiting aptitudes and

predispositions of ones own body to accustom it to performing techniques with full power and

energy”. It is therefore no coincidence that the concept of kimè has also been extended to a further

meaning of “significant strike” or “decisive technique” (“Kime –waza”), as a generic expression of

“determination” and “efficiency”, an expression that is sometimes confused with “Tokui-waza”

which instead represents “ones preferred technique”, that is to say that technique in which someone

is particularly skilled. However, one cannot fail to agree that in all combat disciplines a blow is

considered effective and powerful only if it is carried not only by a limb but by an entire “kinetic

chain” that starts from the ground, involves the whole body (or a good part of it) and ends with the

limb that is going to hit the target. Perhaps not always in the techniques that are performed in many

gyms there is not that kimè someone would expect.... also because some techniques, although

demonstrating their great effectiveness, could not biomechanically express a kimè (e.g. the “Do

Mawashi Kaiten Geri” - forward rolling circular kick)! Moreover, in recent years, there have been

several changes in the training systems in some traditional martial arts also, in order to cope with

new different combat needs. An emblematic example lies in the application of judo techniques in

the case of a generic fighting in which an opponent does not necessarily wear a jacket to hold onto

in order to be able to apply most of the judo techniques. The generic term to identify the garment

for the practice of japanese martial arts is “keikogi” (“uniform for training”) or rather “Dogi”

(“uniform for all people practising Do”, Do “the Way”) as the word “gi” represents precisely the

“kimono” of the practitioner. In recent years a number of Judo and Ju-Jitsu Masters have

“unofficially”developed a huge number of “variants” to the recognized techniques, techniques that

are named with the Anglo-Japanese term “No gi waza” (“techniques without gi”) and truly represent

a new interpretation of fighting in which grappling or grasping an opponents jacket is not

contemplated and, consequently, the fighters do not wear the jacket of the (Do)gi. In truth, the

problem was already known in the past, but then forgotten, and the fighting without a jacket was

called “Ratai-dori”. Even karate, taken it in absolute terms and without establishing any specific

categorisation, has been subject to “variations”. The examination/analysis can begin with different

types of training (and specific practices also) aimed at a greater ability in body mobility and body

displacement, the possibility of using several different techniques of striking and throwing an

opponent, and hence the practical application of techniques using different tactics. In addition to the

traditional equipment for physical conditioning (“renshu”), such as the iron or stone tools of the

Hojo-undo, the makiwara or the sunabukuro (the okinawan punching bag), a considerable number

of different types of “training pads” (pao, punching pads, kick targets, freestanding body

dummies...) and punching bags (both suspended or standing and ground-mounted) have been

produced to train in striking with a full lunge. Particular attention was paid to those exercises that

increase the dynamism of movements and the speed in body shifting,… starting from the

“functional gymnastics”, to increase agility and the motor functions of the body, until the use of

specific equipments such as the “plyometric ladder” (or “agility ladder”, which is the gym version

of the “Jacob’s ladder” used in seamenship). Of a certain importance are also all those high-

intensity training programmes with short recovery periods that go by the name of HIIT (High

Intensity Interval Training): a particularly demanding Japanese HIIT programme is called “Tabata

Training/Workout” (also called “Guerrilla Cardio”) and it is often used for karate training. In

addition, periods of forced isolation due to the Covid-19 pandemic created the need to train

individually, often having to cope with two requirements: the need to train in confined spaces at

home and the need to follow on-line tutorials without having to be too far away from the PC. Thus a

new type of “Tandoku Geiko” (“individual training”) has been developed in order to to perform a

fair number of exercises with the need to perform a training but remaining about in the same

location. In that perspective, the Tandoku Geiko is divided into two types: the “Sonoba Geiko”,

where the exercises are performed almost “on the spot”, and the “Ido Geiko” where the exercises

are performed “along a line”. The ability to move in every direction combined with footwork is

however decisive in a fight, where there is a continuous flow of movements and actions (“rendo-

rensha”) and where the attack does not stop once a single blow has been struck (even if it can be

considered “decisive”) but attacks continue in a very rapid succession of techniques, with blows

and/or throws, until the total annihilation of the opponent. In that context, the movements for the

fight are surely powerful but flexible (“junan-na”) and more swinging than usual. Movements quite

evident observing sets of training sessions where the blows are carried out with the torso in

oscillation, either on the frontal axis or on the sagittal axis, so that the flexion of the torso helps the

kinetic chain of the blow, and the head is in constant motion, becoming a “moving target”. This

greater mobility is also due to the introduction of less rigid techniques and strikes that follow

trajectories for which it is not always easy to parry and it is easier to dodge. A typical example of an

insidious technique is that MMA blow which takes the American word of “overhand”, a descending

parabola punch that is performed at the same time of a lateral dodge of the torso: anyway it is a very

similar technique to others already existing in some karate styles and usually known as “furi uchi”

or “hobutsusen otoshi tsuki” (descending parabolic punch). From an aesthetic point of view, while

remaining extremely dynamic, they are less rigid than traditional karate as they are applied in a

more flexible way by adopting also higher guard positions to ensure greater speed of movement.

Since there is no need to stop actions at the first significant blow and the various techniques are

conceived in a context of continuous movement (“hoko renraku”) affecting various elements that

constitute the technical background for a continuous fighting: the management of the correct

distance to attack (“yuko-maai”), the changes of direction (“henka waza”), the various movements

of the body (“unsoku-waza”, also called “ido-waza”; “tai sabaki” if circular or “tai shintai” if

linear), the lateral shifting (“hiraki ashi”), the movement and shifting (“ire kaeru ashi”), the

bouncing movements (“haneru ashi”), the‘lunging’ techniques (“tobikomi-waza”), the dodging

movements with rotation (“kawashi-waza”, “chowa”), the evasive dodging with the torso only

(“tenshin”), the dodging and bending (“furimi”), the leg or foot sweeping techniques (“kari-waza”),

sweeping techniques (“harai-waza”), the feinting and deception techniques (“kensei/shikake-waza”)

as well as various throwing techniques (“nage waza”). All movements and techniques must be

clearly placed in a broader context of “fighting tactics” (“Kumite Sakusen”). The techniques

adopted in fighting have a strong link with tactics: sometimes it is necessary to establish, according

to the context, which is the most suitable tactic and, consequently, which technique to use...vice

versa, sometimes it is necessary to establish which technique to use and therefore establish the

tactic. The context of karate fighting tactics must be carried out in relation to “timing” (“hyoshi” the

rhythm, understood as “timing”) with which a hypothetical “defender” (that is who “receives” an

attack) attacks/counterattacks a hypothetical “attacker”. That context is codified on the basis of the

“initiative” (“Sen”) of action taken by the “defender” and the consequent timing implemented.

Three levels of initiative, very linked to “perception” (“chikaku”/“yomi”), are identified and then

called “Mitsu no Sen”.

- “Go no Sen”: is the level in which the initiative is left to the attacking opponent. The attacker

launches an attack, the defender defends himself by parrying/ dodging the attack and in turn goes on

the counterattack. The defenders attack action only occurs as a consequence of the attackers

initiative. Time and distance only allow a reaction to be decided once the attacker has already

started the attack. The tactical term is “defensive play action”.

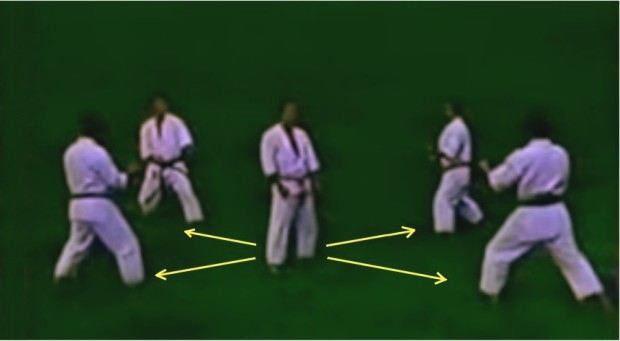

- “Sen no Sen” (also called “Sen no Go”, or even “Tai no Sen”). There are different situations

covered in this type of initiative: the defenders initiative is immediate, at the slightest movement of

the attacker the defender takes the initiative and attacks directly, or he parries/ dodges a blow and

simultaneously counterattacks. The action appears simultaneous as the defenders attack has a very

slight “in advance of action” (“Sen te”) on the attackers attack. The defender also assumes the

tactical definition of “tackle action player”, as he immediately faces the opponents attack in

(almost) simultaneous action, assuming for sure that for everyone it is impossible to attack and

defend at the same time.

- “Sen Sen no Sen” (also called “Ken no Sen”). The defenders initiative is maximised and the

tactical term is “pre-emptive defence”. A pre-emptive attack is based on an individuals predictive

feeling, a “perception” of the opponents imminent attack or the attack intention. It represents the

ultimate expression of “taking the iniziative” (“Sen-wo-toru”).

There is a point of fusion between the traditional and the innovative through the tactics that are

adopted both because of the context in which they must be applied and because of the individual

predisposition towards specific techniques and tactics. Lastly, it is good to remember that “everyone

must grow up individually”, a concept that is summed up with the term “Shuhari”: “Shu”, learning

by following and observing the masters precepts; “Ha”, understanding and mastering the

techniques and teachings acquired; “Ri”, following ones own path taking into account ones own

interpretation of the techniques and tactics in full harmony with ones physical and mental skill and

aptitude in order to achieve ones own objectives.

Before addressing the subject of “Combat Karate” in its various and articulated aspects, it is

necessary to clarify “what Combat Karate is not.” First of all, Combat Karate is not a new style of

karate but it is a term basically used to describe a different kind of “karate approach for fighting”,

an approach that requires different forms of training and that develops new and effective

techniques, albeit sometimes performed in ways that do not properly fit those criteria imposed by

traditional karate. There is still no official definition of it, perhaps because its exact position

between tradition and innovation has yet to be established, and perhaps for that reason there are

several definitions to attempt a categorization. The simplest one is clearly “karate for combatting”

...but is there any karate style that is not “for combatting” ???

As a preliminary point, it must be emphasised that “Combat Karate” is not “Karate Combat”.

Karate Combat (KC) indeed is a famous commercial brand, one brand among many (K1, UFC...),

which promotes professional karate fights in “full contact fighting” (i.e. without the control of

blows), without distinction of styles of origin or schools. In recent years, in fact, the world of

combat sports, and Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) in particular, have promoted, through numerous

associations, federations and sports organisations, various types of championships, competitions

and tournaments at a professional level (with different criteria for awarding victory, scoring

schemes, competition regulations, techniques allowed or not, the possibility of wearing protections

or gloves....), causing the proliferation of numerous television entertainment “formats” that

capitalise even several millions of dollars per year on the Stock Market.

The development of full-contact fighting in the “combat sports” has long since taken place within a

fair number of karate styles (e.g. Kyokushin, Shidokan, Shindenkai, Seidokaikan, Ashihara,

Enshin...) as well as relatively more recent karate styles that also involve the use of throwing

techniques and grappling techniques (Ashigaru-Ryu Karate, Seireikan Karate, Kudo/Karate Daido

Juku/Kakuto Karate, Nihon Zendokai.... ) leading karate, in general terms, to implement innovative

modifications both in terms of training development and in terms of enriching its technical wealth

of knowledge with the acquisition of techniques from other combat disciplines (e.g. the “fukubi

tomeru geri” - kick to the abdomen, or hips, to block the opponents forward movement using a

kick similar to a tiip (kick) used in the Thai discipline of Muai Lert Rit).

Obviously, the technical validity of these forms of fighting, beyond the constraints of sporting

application, has allowed the various karateka to successfully face even those fighters who employ

numerous techniques from different disciplines, including that mixture of martial arts known in

Japan as “Sogo Kakutogi” (“Composite Combat” or “Composite Fighting”). Leaving aside now the

purely sporting aspects, the fact remains that the so-called “traditional” karate has itself also been

subject to a certain amount of innovations both in terms of training and in terms of interpretation of

techniques, emphasizing points of solidity from tradition while at the same time introducing

innovative concepts in both techniques and training methods. Certainly a number of karate Masters

have had to smooth over, even with themselves, points of disagreement in order to harmonize the

“old” with the “new” in order to evolve, as it happens in any art or discipline whose intent is to

progress towards further and significant developments.

But let us return to Combat Karate by identifying what exactly it means by observing three aspects:

the training, how the techniques are carried out and therefore the resultant combat tactics. There are

clearly links with various styles and schools of karate, but it will be the personal experience of the

individual reader to identify and decide affinities and differences.

As a preliminary, it is necessary to deal with a much-debated topic, namely that of “kimè” and what

it entails in the “power generation of the strike”. The word kimè is one of those words that can have

many meanings, although sometimes only a few are considered enough to provide a sufficiently

comprehensive explanation. In fact, the word kimè is translated with a dozen different meanings,

but the most common ones are; “intention”, “decision”, “contraction”, “focal point of

concentration”, “impact”, “power”. Actually, kimé is a concept of both Chinese (fa jing) and

Okinawese (chinkuchi / muchimi) derivation and now it is found almost exclusively in Japanese

martial arts. Leaving aside the complex oriental theories on the creation and transfer of energy,

however, it is not easy to univocally define kimè and it is simpler to explain its meaning: kimè

represents a point of maximum concentration in which the mind, body and spirit combine together

to instantaneously direct the maximum power of a strike onto a target by using ones own inner

energy (ki) rising from the abdominal area (hara/tanden).

This is an effective and instantaneous transfer of kinetic energy from ones body to the target which

is achieved through a very rapid contraction and subsequent immediate relaxation of muscles,

tendons and nerves, often exploiting the rotation or movement of the hips (koshino kaiten). The

aesthetic result is that rapid “robotic-mechanical” movement with which a blow is instantly

blocked, as is particularly highlighted in the practice of kata or kihon. That “robotic” movement

allows a greater transfer of destructive energy onto the target, guaranteeing a better balance of the

body and safeguarding the joints of the arms or legs from possible injuries caused by those violent

and immediate hyperextension of the muscles, tendons and nerves. This concept is extremely

divisive among martial arts practitioners as many combat disciplines, which do not use kimé, but

develop nevertheless extremely powerful strikes by delivering the same strikes “in a lunge way”,

without having to “block” a strike (theoretically “before the target”, or “on the target” or “a little

beyond the target”), through that contraction required by traditional karate to achieve the famous

“good kimé”. For the traditional approach indeed (initially based on “no-sporting aims”) not having

a good kimé means “not having a technique to be considered powerful and effective”. Certainly

nobody would dream of stopping a hammer blow while hammering nails or stopping an axe blow

while chopping wood to make the blow more powerful, but those are clearly different concepts of

the application of force and power. Obviously over time many arguments have been made, both for

and against kimé, but perhaps the best way, as the Okinawan Grandmaster Shoshin Nagamine (of

the Matsubayashi Shorin-Ryu Karate / founder of the martial art of Taido) suggested, to overcome

this thorny argument lies in practising karate considering kimè as “a fundamental personal

experience” or “an added value” to achieve a karate of excellence, without ever precluding new

“adaptations” of enrichment, development and improvement by “exploiting aptitudes and

predispositions of ones own body to accustom it to performing techniques with full power and

energy”. It is therefore no coincidence that the concept of kimè has also been extended to a further

meaning of “significant strike” or “decisive technique” (“Kime –waza”), as a generic expression of

“determination” and “efficiency”, an expression that is sometimes confused with “Tokui-waza”

which instead represents “ones preferred technique”, that is to say that technique in which someone

is particularly skilled. However, one cannot fail to agree that in all combat disciplines a blow is

considered effective and powerful only if it is carried not only by a limb but by an entire “kinetic

chain” that starts from the ground, involves the whole body (or a good part of it) and ends with the

limb that is going to hit the target. Perhaps not always in the techniques that are performed in many

gyms there is not that kimè someone would expect.... also because some techniques, although

demonstrating their great effectiveness, could not biomechanically express a kimè (e.g. the “Do

Mawashi Kaiten Geri” - forward rolling circular kick)! Moreover, in recent years, there have been

several changes in the training systems in some traditional martial arts also, in order to cope with

new different combat needs. An emblematic example lies in the application of judo techniques in

the case of a generic fighting in which an opponent does not necessarily wear a jacket to hold onto

in order to be able to apply most of the judo techniques. The generic term to identify the garment

for the practice of japanese martial arts is “keikogi” (“uniform for training”) or rather “Dogi”

(“uniform for all people practising Do”, Do “the Way”) as the word “gi” represents precisely the

“kimono” of the practitioner. In recent years a number of Judo and Ju-Jitsu Masters have

“unofficially”developed a huge number of “variants” to the recognized techniques, techniques that

are named with the Anglo-Japanese term “No gi waza” (“techniques without gi”) and truly represent

a new interpretation of fighting in which grappling or grasping an opponents jacket is not

contemplated and, consequently, the fighters do not wear the jacket of the (Do)gi. In truth, the

problem was already known in the past, but then forgotten, and the fighting without a jacket was

called “Ratai-dori”. Even karate, taken it in absolute terms and without establishing any specific

categorisation, has been subject to “variations”. The examination/analysis can begin with different

types of training (and specific practices also) aimed at a greater ability in body mobility and body

displacement, the possibility of using several different techniques of striking and throwing an

opponent, and hence the practical application of techniques using different tactics. In addition to the

traditional equipment for physical conditioning (“renshu”), such as the iron or stone tools of the

Hojo-undo, the makiwara or the sunabukuro (the okinawan punching bag), a considerable number

of different types of “training pads” (pao, punching pads, kick targets, freestanding body

dummies...) and punching bags (both suspended or standing and ground-mounted) have been

produced to train in striking with a full lunge. Particular attention was paid to those exercises that

increase the dynamism of movements and the speed in body shifting,… starting from the

“functional gymnastics”, to increase agility and the motor functions of the body, until the use of

specific equipments such as the “plyometric ladder” (or “agility ladder”, which is the gym version

of the “Jacob’s ladder” used in seamenship). Of a certain importance are also all those high-

intensity training programmes with short recovery periods that go by the name of HIIT (High

Intensity Interval Training): a particularly demanding Japanese HIIT programme is called “Tabata

Training/Workout” (also called “Guerrilla Cardio”) and it is often used for karate training. In

addition, periods of forced isolation due to the Covid-19 pandemic created the need to train

individually, often having to cope with two requirements: the need to train in confined spaces at

home and the need to follow on-line tutorials without having to be too far away from the PC. Thus a

new type of “Tandoku Geiko” (“individual training”) has been developed in order to to perform a

fair number of exercises with the need to perform a training but remaining about in the same

location. In that perspective, the Tandoku Geiko is divided into two types: the “Sonoba Geiko”,

where the exercises are performed almost “on the spot”, and the “Ido Geiko” where the exercises

are performed “along a line”. The ability to move in every direction combined with footwork is

however decisive in a fight, where there is a continuous flow of movements and actions (“rendo-

rensha”) and where the attack does not stop once a single blow has been struck (even if it can be

considered “decisive”) but attacks continue in a very rapid succession of techniques, with blows

and/or throws, until the total annihilation of the opponent. In that context, the movements for the

fight are surely powerful but flexible (“junan-na”) and more swinging than usual. Movements quite

evident observing sets of training sessions where the blows are carried out with the torso in

oscillation, either on the frontal axis or on the sagittal axis, so that the flexion of the torso helps the

kinetic chain of the blow, and the head is in constant motion, becoming a “moving target”. This

greater mobility is also due to the introduction of less rigid techniques and strikes that follow

trajectories for which it is not always easy to parry and it is easier to dodge. A typical example of an

insidious technique is that MMA blow which takes the American word of “overhand”, a descending

parabola punch that is performed at the same time of a lateral dodge of the torso: anyway it is a very

similar technique to others already existing in some karate styles and usually known as “furi uchi”

or “hobutsusen otoshi tsuki” (descending parabolic punch). From an aesthetic point of view, while

remaining extremely dynamic, they are less rigid than traditional karate as they are applied in a

more flexible way by adopting also higher guard positions to ensure greater speed of movement.

Since there is no need to stop actions at the first significant blow and the various techniques are

conceived in a context of continuous movement (“hoko renraku”) affecting various elements that

constitute the technical background for a continuous fighting: the management of the correct

distance to attack (“yuko-maai”), the changes of direction (“henka waza”), the various movements

of the body (“unsoku-waza”, also called “ido-waza”; “tai sabaki” if circular or “tai shintai” if

linear), the lateral shifting (“hiraki ashi”), the movement and shifting (“ire kaeru ashi”), the

bouncing movements (“haneru ashi”), the‘lunging’ techniques (“tobikomi-waza”), the dodging

movements with rotation (“kawashi-waza”, “chowa”), the evasive dodging with the torso only

(“tenshin”), the dodging and bending (“furimi”), the leg or foot sweeping techniques (“kari-waza”),

sweeping techniques (“harai-waza”), the feinting and deception techniques (“kensei/shikake-waza”)

as well as various throwing techniques (“nage waza”). All movements and techniques must be

clearly placed in a broader context of “fighting tactics” (“Kumite Sakusen”). The techniques

adopted in fighting have a strong link with tactics: sometimes it is necessary to establish, according

to the context, which is the most suitable tactic and, consequently, which technique to use...vice

versa, sometimes it is necessary to establish which technique to use and therefore establish the

tactic. The context of karate fighting tactics must be carried out in relation to “timing” (“hyoshi” the

rhythm, understood as “timing”) with which a hypothetical “defender” (that is who “receives” an

attack) attacks/counterattacks a hypothetical “attacker”. That context is codified on the basis of the

“initiative” (“Sen”) of action taken by the “defender” and the consequent timing implemented.

Three levels of initiative, very linked to “perception” (“chikaku”/“yomi”), are identified and then

called “Mitsu no Sen”.

- “Go no Sen”: is the level in which the initiative is left to the attacking opponent. The attacker

launches an attack, the defender defends himself by parrying/ dodging the attack and in turn goes on

the counterattack. The defenders attack action only occurs as a consequence of the attackers

initiative. Time and distance only allow a reaction to be decided once the attacker has already

started the attack. The tactical term is “defensive play action”.

- “Sen no Sen” (also called “Sen no Go”, or even “Tai no Sen”). There are different situations

covered in this type of initiative: the defenders initiative is immediate, at the slightest movement of

the attacker the defender takes the initiative and attacks directly, or he parries/ dodges a blow and

simultaneously counterattacks. The action appears simultaneous as the defenders attack has a very

slight “in advance of action” (“Sen te”) on the attackers attack. The defender also assumes the

tactical definition of “tackle action player”, as he immediately faces the opponents attack in

(almost) simultaneous action, assuming for sure that for everyone it is impossible to attack and

defend at the same time.

- “Sen Sen no Sen” (also called “Ken no Sen”). The defenders initiative is maximised and the

tactical term is “pre-emptive defence”. A pre-emptive attack is based on an individuals predictive

feeling, a “perception” of the opponents imminent attack or the attack intention. It represents the

ultimate expression of “taking the iniziative” (“Sen-wo-toru”).

There is a point of fusion between the traditional and the innovative through the tactics that are

adopted both because of the context in which they must be applied and because of the individual

predisposition towards specific techniques and tactics. Lastly, it is good to remember that “everyone

must grow up individually”, a concept that is summed up with the term “Shuhari”: “Shu”, learning

by following and observing the masters precepts; “Ha”, understanding and mastering the

techniques and teachings acquired; “Ri”, following ones own path taking into account ones own

interpretation of the techniques and tactics in full harmony with ones physical and mental skill and

aptitude in order to achieve ones own objectives.

KATA: a much hermetic topic

It is well known to all, every subject in the field of karate has an encyclopaedic scope, and the

subject of “kata” is no different. To make the subject difficult, as well as very articulate, is the fact

that many historical aspects of karate go back to a distant past from which it is now difficult to have

reliable data due to undetermined circumstances, events, dates and places have not clear references

both in time and/or in official documents. In addition to what that has just been said, kata also have

sometimes indetermined and sometimes even mysterious aspects. But what exactly is a kata? That

is a good and not trivial question. The word Kata has several meanings in the Japanese language

and in this case means “form” and represents, together with Kihon (basic exercises of techniques)

and Kumite (combat/sparring), one of the three pillars on which the practice of karate is historically

based on. In concise terms kata can be defined as “a carefully codified and timed sequence of

specific and interlocked “moves” (techniques, movements, shifts, stops, rotations, change of

directions), usually performed alone which reproduces a combat pattern against one or more

opponents (attacking from different directions) in order to develop and perfect the karateka’s

fighting techniques, concentration, breathing, muscle contractions, rhythm, balance, speed, strike

control, strenght and power”.

The concept of kata is completely unknown in Western fighting systems and is to be considered as a

typical expression of Far-East martial arts. Kata are very common in different Asian countries

where every combat style or school have its own number of kata, with different names, sometime

with many technical similarities. Kata reflect the various technical characteristics of the style/school

to which they belong: there are speed kata, power kata, breathing kata or others that are an amalgam

of various tendencies. Many things have been said about their similar or dissimilar aesthetic canons

and how they have been handed down in such a cryptic manner, not as if they were just combat

exercises but rather as they were a sort of war dances or ritual dances with hidden inside fighting

techniques to be interpreted (or discovered!). As we will see, kata have different levels of

complexity and, beyond the rigid codifications, the masters who created the original versions have

deliberately left to future masters some interpretative spaces for different “technical interpretations”

to apply in real combat. Those interpretations, generally known as bunkai are indeed a

demonstration or application of the kata in combat situation. Incidentally, there is no single

interpretation of a kata, no single bunkai, and each master may have a personal vision, explanation,

meaning and interpretation of it. There are indeed three levels of “move away” from origin

(kaisetsu, kaishaku and bunkai) representing a gradual detachment from the original meaning, from

the “essence” of kata (kukuchi). Some karate masters also established 3 bunkai levels of “in-depht

technical”: omote, ura and honto. For that reason it is necessary to know the true meaning of all

moves inside kata, its “soul” and its contents, and not thinking that it is merely a gestual code for its

own sake, a sort of coded “shadowboxing” or a useless reproduction of movements whose possible

application in real combat is inapplicable. Furthermore, the mental concentration required in the

execution of a kata means that the kata itself could be regarded as a form of “dynamic meditation”

likening it to the more classical form of “static meditation” as practiced in both Zen and Yoga. One

often wonders how many kata exist. There are currently more than 150 kata belonging to different

styles practiced all around the world but those officially recognised by the World Karate Federation

(WKF), to be performed in competitions, number around a hundred. Generally speaking, a classical

karate style has a technical background of around 30 kata from the basic to the more advanced ones.

Just the Shito-Ryu goes up to more than 60 kata. Taking into consideration the large number of kata

that each style possesses, it is appropriate to refer to an old Japanese saying that goes “a kata every

3 years” (kata hitotsu sannen) and that implies it takes 3 years for a kata to be fully assimilated and

understood....illustrating the many years needed to master all kata of one style! Often where kata is

concerned, the word “hokei” also appears, a word that has fallen into disuse but from a purely

doctrinal point of view, kata represents a sequence of moves all technically connected whereas

hokei represents just a sum of individual techniques added together but without a precise technical

meaning.

However, within the various codifications established by the various styles for their kata, there are

structural elements that can vary within certain parameters, namely: the path, the moves and the

kiai.

The path. A common factor in almost all kata is that their execution follows a well-established and

codified path (which is obviously specific for each kata) called embusen. Embusen should

start and finish in the same point (kiten). For executing a kata the area required varies from 2 meter

square area up to 8 meter square area. For "Kata competitions" additional 2 metres on all sides (of

the 8x8 area) are added, as a safety area.

The moves. By moves we mean all the various movements and steps which, joined together, create

the entire kata. Some kata has approximately just 10 moves (as in the old Motobu-Ryu) and some

others can have more than 90 moves. For example one of the most popular and advanced kata

(called “Suparinpei” in Goju-Ryu and Shito-Ryu, “Hyakuhachiho” in Shotokan) goes on 108

moves.

The Kiai. As well known, kiai is a vast subject but briefly for now it indicates the explosive spirited

shout that is used to focus energy when performing an attacking or defending move. In all kata the

techniques that are “reinforced” with kiai are rigidly established. In any kata the techniques

reinforced with kiai are generally only two, at most three. It is passed down that there should also be

some “hidden silent kiai points” where a kind of “silent kiai” (kensei) is applied.

Structural and common elements of kata generally consider the following:

Seika-tanden. The control of the “body's center of gravity and energy” (tanden) contracting the

inner muscles of the abdomen and controlling the body posture during the performance. It

represents the “hip vibration”. Generally applied at movement or body or hip rotation.

Koshino (koshino-kaiten). It represents the “hip rotation”, a rotation of the hips which can be

applied in the direction of the blow or in the opposite direction: it depends on the type of strike

connected to the striking position. Some Okinawan schools also use the “double rotation” (bai-

koshino) of the hips towards the unique direction of attack (involving two very rapid hip

movements in counter-phase).

Kimè. Kimè means the use of the power at the right moment tensing and contracting

contemporarily the correct muscles, nerves and tendons during the execution of a technique. In

Okinawan karate styles a similar concept of kimè is named chinkuchi. Generally applied at any

strike and block but linked to the number of specific moves. The kimè is connected to the concept

of own concentration to attack (kiotsuke) and own counterforce or recoil of arm (hikitè).

Nogare. The complex theories on the birth and focus of energy applied in the martial arts are linked

to some forms of breathing. There are rhythmic and deep abdominal breathing techniques that focus

energy (haragei). From a normal chest-breathing (taiki) does exist a form of hard breathing which

aids the dynamic inner tension of abdomen to convey energy. That type of breathing is called ibuki

(that is an abdominal-breathing). That hard style of breathing, a noisy breathing technique made with

a long exhalation and ends with a short breath, is called “yo-ibuki” or better “nogare”. There are the so-

called “breathing-only kata” where the whole body remains stiffened and there are just few body

movements always in extreme muscle contraction or tension (tensho).

Koka. Koka means “effectiveness” and doctrinally speaking is the sum of koshino, seika-tanden, kimè

and nogare.

Kyoshi. Kyoshi represents the rhythm, the cadence of a series of movements which are going to

determine the correct timing of an action (that is hazumi: the correct timing).

Maai. Maai means “distance” and is related to both space and time. Space because distance

represents that space to be run across and time because distance also represents the time taken to

run across that space.

Messen. Messen is a principle by which the visual contact with the enemy/opponent must always be

sought. During a kata performance, with virtual opponent, messen must nevertheless be pursued.

There are several ways to categorize kata but the main is by level of difficulty (4 levels, obviously

used also as a requirement for upgrading during “belt to belt” examinations):

1. propaedeutic: didactic for physical training;

2. intermediate: didactic for physical conditioning;

3. classic: with development of basic and intermediate fighting techniques of the style of belonging;

4. advanced: with development of advanced fighting techniques of the style of belonging.

It must not be forgotten that the historical development of kata was greatly infuenced by the ancient

karate origin: the Shorei current (from which have arisen those styles that privilege muscular power

and physical strenght) and the Shorin current (from which have arisen those styles that privilege

speed and agility). All kata indeed express both strength and power as well as speed and agility, so

it is not so easy to establish their true origin if they are not known by stylistic differences. A

separate question are the “breathing-only” kata which are obviously of Shorei origin.

Currently, hightly effective western fighting arts/systems and new emerging highly effective karate

styles do not include kata in their training programs or do not give emphasis to the practice. In

modern times of “everything and immediately” a long kata training is considered a waste of time

and that is a big and debated question!

Anyhow, all that has been said here about kata, believing or not believing, can be considered as a

cultural experience, a cultural background for any old karateka and remembering that a kata without

soul is just a calisthenic exercise.

It is well known to all, every subject in the field of karate has an encyclopaedic scope, and the

subject of “kata” is no different. To make the subject difficult, as well as very articulate, is the fact

that many historical aspects of karate go back to a distant past from which it is now difficult to have

reliable data due to undetermined circumstances, events, dates and places have not clear references

both in time and/or in official documents. In addition to what that has just been said, kata also have

sometimes indetermined and sometimes even mysterious aspects. But what exactly is a kata? That

is a good and not trivial question. The word Kata has several meanings in the Japanese language

and in this case means “form” and represents, together with Kihon (basic exercises of techniques)

and Kumite (combat/sparring), one of the three pillars on which the practice of karate is historically

based on. In concise terms kata can be defined as “a carefully codified and timed sequence of

specific and interlocked “moves” (techniques, movements, shifts, stops, rotations, change of

directions), usually performed alone which reproduces a combat pattern against one or more

opponents (attacking from different directions) in order to develop and perfect the karateka’s

fighting techniques, concentration, breathing, muscle contractions, rhythm, balance, speed, strike

control, strenght and power”.

The concept of kata is completely unknown in Western fighting systems and is to be considered as a

typical expression of Far-East martial arts. Kata are very common in different Asian countries

where every combat style or school have its own number of kata, with different names, sometime

with many technical similarities. Kata reflect the various technical characteristics of the style/school

to which they belong: there are speed kata, power kata, breathing kata or others that are an amalgam

of various tendencies. Many things have been said about their similar or dissimilar aesthetic canons

and how they have been handed down in such a cryptic manner, not as if they were just combat

exercises but rather as they were a sort of war dances or ritual dances with hidden inside fighting

techniques to be interpreted (or discovered!). As we will see, kata have different levels of

complexity and, beyond the rigid codifications, the masters who created the original versions have

deliberately left to future masters some interpretative spaces for different “technical interpretations”

to apply in real combat. Those interpretations, generally known as bunkai are indeed a

demonstration or application of the kata in combat situation. Incidentally, there is no single

interpretation of a kata, no single bunkai, and each master may have a personal vision, explanation,

meaning and interpretation of it. There are indeed three levels of “move away” from origin

(kaisetsu, kaishaku and bunkai) representing a gradual detachment from the original meaning, from

the “essence” of kata (kukuchi). Some karate masters also established 3 bunkai levels of “in-depht

technical”: omote, ura and honto. For that reason it is necessary to know the true meaning of all

moves inside kata, its “soul” and its contents, and not thinking that it is merely a gestual code for its

own sake, a sort of coded “shadowboxing” or a useless reproduction of movements whose possible

application in real combat is inapplicable. Furthermore, the mental concentration required in the

execution of a kata means that the kata itself could be regarded as a form of “dynamic meditation”

likening it to the more classical form of “static meditation” as practiced in both Zen and Yoga. One

often wonders how many kata exist. There are currently more than 150 kata belonging to different

styles practiced all around the world but those officially recognised by the World Karate Federation

(WKF), to be performed in competitions, number around a hundred. Generally speaking, a classical

karate style has a technical background of around 30 kata from the basic to the more advanced ones.

Just the Shito-Ryu goes up to more than 60 kata. Taking into consideration the large number of kata

that each style possesses, it is appropriate to refer to an old Japanese saying that goes “a kata every

3 years” (kata hitotsu sannen) and that implies it takes 3 years for a kata to be fully assimilated and

understood....illustrating the many years needed to master all kata of one style! Often where kata is

concerned, the word “hokei” also appears, a word that has fallen into disuse but from a purely

doctrinal point of view, kata represents a sequence of moves all technically connected whereas

hokei represents just a sum of individual techniques added together but without a precise technical

meaning.

However, within the various codifications established by the various styles for their kata, there are

structural elements that can vary within certain parameters, namely: the path, the moves and the

kiai.

The path. A common factor in almost all kata is that their execution follows a well-established and

codified path (which is obviously specific for each kata) called embusen. Embusen should

start and finish in the same point (kiten). For executing a kata the area required varies from 2 meter

square area up to 8 meter square area. For "Kata competitions" additional 2 metres on all sides (of

the 8x8 area) are added, as a safety area.

The moves. By moves we mean all the various movements and steps which, joined together, create

the entire kata. Some kata has approximately just 10 moves (as in the old Motobu-Ryu) and some

others can have more than 90 moves. For example one of the most popular and advanced kata

(called “Suparinpei” in Goju-Ryu and Shito-Ryu, “Hyakuhachiho” in Shotokan) goes on 108

moves.

The Kiai. As well known, kiai is a vast subject but briefly for now it indicates the explosive spirited

shout that is used to focus energy when performing an attacking or defending move. In all kata the

techniques that are “reinforced” with kiai are rigidly established. In any kata the techniques

reinforced with kiai are generally only two, at most three. It is passed down that there should also be

some “hidden silent kiai points” where a kind of “silent kiai” (kensei) is applied.

Structural and common elements of kata generally consider the following:

Seika-tanden. The control of the “body's center of gravity and energy” (tanden) contracting the

inner muscles of the abdomen and controlling the body posture during the performance. It

represents the “hip vibration”. Generally applied at movement or body or hip rotation.

Koshino (koshino-kaiten). It represents the “hip rotation”, a rotation of the hips which can be

applied in the direction of the blow or in the opposite direction: it depends on the type of strike

connected to the striking position. Some Okinawan schools also use the “double rotation” (bai-

koshino) of the hips towards the unique direction of attack (involving two very rapid hip

movements in counter-phase).

Kimè. Kimè means the use of the power at the right moment tensing and contracting

contemporarily the correct muscles, nerves and tendons during the execution of a technique. In

Okinawan karate styles a similar concept of kimè is named chinkuchi. Generally applied at any

strike and block but linked to the number of specific moves. The kimè is connected to the concept

of own concentration to attack (kiotsuke) and own counterforce or recoil of arm (hikitè).

Nogare. The complex theories on the birth and focus of energy applied in the martial arts are linked

to some forms of breathing. There are rhythmic and deep abdominal breathing techniques that focus

energy (haragei). From a normal chest-breathing (taiki) does exist a form of hard breathing which

aids the dynamic inner tension of abdomen to convey energy. That type of breathing is called ibuki

(that is an abdominal-breathing). That hard style of breathing, a noisy breathing technique made with

a long exhalation and ends with a short breath, is called “yo-ibuki” or better “nogare”. There are the so-

called “breathing-only kata” where the whole body remains stiffened and there are just few body

movements always in extreme muscle contraction or tension (tensho).

Koka. Koka means “effectiveness” and doctrinally speaking is the sum of koshino, seika-tanden, kimè

and nogare.

Kyoshi. Kyoshi represents the rhythm, the cadence of a series of movements which are going to

determine the correct timing of an action (that is hazumi: the correct timing).

Maai. Maai means “distance” and is related to both space and time. Space because distance

represents that space to be run across and time because distance also represents the time taken to

run across that space.

Messen. Messen is a principle by which the visual contact with the enemy/opponent must always be

sought. During a kata performance, with virtual opponent, messen must nevertheless be pursued.

There are several ways to categorize kata but the main is by level of difficulty (4 levels, obviously

used also as a requirement for upgrading during “belt to belt” examinations):

1. propaedeutic: didactic for physical training;

2. intermediate: didactic for physical conditioning;

3. classic: with development of basic and intermediate fighting techniques of the style of belonging;

4. advanced: with development of advanced fighting techniques of the style of belonging.

It must not be forgotten that the historical development of kata was greatly infuenced by the ancient

karate origin: the Shorei current (from which have arisen those styles that privilege muscular power

and physical strenght) and the Shorin current (from which have arisen those styles that privilege

speed and agility). All kata indeed express both strength and power as well as speed and agility, so

it is not so easy to establish their true origin if they are not known by stylistic differences. A

separate question are the “breathing-only” kata which are obviously of Shorei origin.

Currently, hightly effective western fighting arts/systems and new emerging highly effective karate

styles do not include kata in their training programs or do not give emphasis to the practice. In

modern times of “everything and immediately” a long kata training is considered a waste of time

and that is a big and debated question!

Anyhow, all that has been said here about kata, believing or not believing, can be considered as a

cultural experience, a cultural background for any old karateka and remembering that a kata without

soul is just a calisthenic exercise.

KARATE: A diamond with many new facets

By Sensei Bandioli WKKO Italia

Generally speaking, everyone who has studied and practiced (or has been studying and practicing) a fighting discipline has clearly in his/her mind that any kind of discipline has its own culture, historical background, ethical rules, concepts and technical expertize and knowledge. However from ancient times till now all round the world, and expecially taking into consideration the East and the West, the approaches to fighting disciplines are very different, particularly such as in Japan. Japanese culture consists of many aspects under rigorous codes as abiding by severe rules of behavior or following strictly procedures - just think of Chado (tea ceremony), Shodo (art of calligraphy), Ikebana (art of flowers arrangements), Origami (art of folding paper), Bonsai (art of growing miniature trees), Karesansui (art of making and raking a Zen garden) and, the last but not the least, the Japanese martial arts (Karate-do, Kobudo, Judo, Aikido, Kendo, Kyudo, Iaido…). The martial arts, as any kind of art or discipline, have their own pillars rooted in tradition with their own doctrine, techniques, terminology, behaviours, rites and rituals, but, contextually, are subject to continuing enrichments, developments, individual interpretations and, sometimes, few changes… that is to say, an “evolution” over time. Karate, for exemple, had its origin in the Island of Okinawa (with just four schools and relative styles), and subsequently, after the acquisition of Okinawa and its arcipelago by Japan (1879), had itself undergone great development through the creation and development of furher styles reaching the number, more or less, of about twenty of them. After the end of the Second World War, due to a japanese political will, karate spread all over the world thanks to a great transfer overseas of japanese karate masters adding, over the years, more and more styles, some of them too much “Westernized” (in the opinion of many “purists”) because of the abandonment of traditions and technical dogmas of the early “Founders” of karate schools. At the moment in the world the most authoritative styles are about forty over a number of about a hundred, if not more. So how many types of karate do exist? Before addressing this issue, it is appropriate to make a few disquisitions as the Oriental people often say that karate is like a diamond: the core is unique but it has many facets all around. There are a few approaches, both historical and technical, that allow us to correctly frame the continuation of further considerations. There are various initial approaches that allow karate to be categorised in different ways, but mainly in accordance with: martial aims and purposes (Bugei, Budo and Kakugi concepts), ancient origins (Shorin and Shorei currents), ancient technical roots (Okinawan karate and Japanese karate schools and styles) and technical training and fighting rules (Traditional Karate and Modern Karate). As it is well known, each of the topics mentioned have an encyclopaedic dimension and summarising them in a few lines is not an easy task and a pragmatic approach is mandatory, even if it might sound superficial. Moreover, some of the topics which now are being considered are very argued topics and source of great debates and heated discussion among historians, scholars and pratictioners of all levels.

Bugei, Budo and Kakugi concepts. This is the approach by which a martial art is considered in accordance to the aims and purposes to be pursued: Bugei represents the practice of a martial art to achieve offensive skills and lethal capabilities for warfighting, that is to develop a combat discipline for the battlefield; Budo represents the practice of a martial art to achieve, as far as possible, the perfection of the balance of oneself through a rigorous discipline, hard training and physical conditioning, in order to became a better and strong human being; and Kakugi represents a far more recent concept that is the practice of a martial art solely and exclusively for sporting purposes.

Shorin and Shorei currents. These two ancient currents represent probably the origin of two main types of chinese fighting school, a synthesis of many other forms of fighting, which arrived in the Island of Okinawa and contributed to the creation of two different ways to teach (schools/styles) and practice karate: the Shorin-Ryu, from which arose all those karate styles that privilege agility and speed, and the Shorei-Ryu, from which arose all those karate styles that privilege muscular power and physical strenght. Indeed any karate style actually represent a harmonic fusion of all those features as agility, speed, balance, power, strength…and much more!

Okinawan karate and Japanese karate. Even though the Island of Okinawa (and its archipelago) has been Japanese for more than a century, there still remain many differences between Okinawan karate and Japanese karate. All those differences, that strongly affect descendant schools and styles, concern almost all aspects of karate: body conditioning exercises, traditional “basics” (kihon), body movements, training and “traditional forms” (kata), types of breathing, development of power, fighting techniques (kumite), terminology and combat tactics.

Traditional Karate and Modern Karate.The concept distinguishing a karate of tradition from a modern karate is a bit of a misnomer as the so-called “traditional karate” has also modernised itself and expanded considerably the fighting techniques, while remaining strongly tied to tradition. The main difference lies in the fact that “modern karate” means a karate aimed at sporting competitions which could also easily be called “sport karate”. In fact, sport karate has evolved as a sport strongly influenced both by the numerous types of encounters (inter-style, i.e. between different styles of karate, against other martial arts or fighting discipline), by the possibility of striking the opponent (controlled blow, semi-contact, full-contact...), by the constraints imposed (with protections, without protections, gloved hand, bare hand....) and by the relative rules of the various tournaments or championships (constraints, bans, prohibited techniques....). Furthermore, with the development of new forms of combat sports, such as MMA (Mixed Martial Arts), sometimes referred to as “Cage Fighting”, “Ultimate Fighting” or “No Holds Barred” (incorporating techniques from various oriental martial arts and from other different full-contact combat sports), there has been, even in some karate schools, a greater distancing from traditional forms of training in favour of a kind of more pragmatic and more immediate training for achieving quick results. For that reason it is no surprise if the new emerging karate styles or fighting systems do not give emphasis to the practice of ancient and traditional katas at the fact that many hightly effective fighting arts/systems do not include katas in their training programs (sometimes katas are unkown in nature). All that said, taking for granted the enormous value of katas for the development of karateka's concentration, strike control, breathing, rhythm, speed, balance, strength, and power. In Japan, in truth, there was already a form of mixed martial arts (for sporting purposes only) called Sogo Kakutogi where hitting, knocking down and hitting again an opponent (utsu-taosu-utsu) were envisaged in exactly the same way as now in MMA (defined “ground and pound”).

All this has been said just to introduce the fact that there is another method for categorising karate (but also other forms of martial arts, of course), namely the one called “by aim”, bearing in mind what purpose karate is practised for. This kind of classification, attributable to an unspecified Japanese karate Master, is not to be taken as a tautology (that is “a truth by definition”) but it can be considered quite appropriate. According to this concept, karate can be categorised “by purposes” (imi), regardless of the style practised or school of origin, and can roughly divided into the following categories (some aspects of which are sometimes partially overlapping):

- Koryu karate: all styles that follow an ancient “martial tradition”, better known as Do, a way/discipline that tends towards inner perfecting, through spiritual, ethical and moral development by means of an assiduous, rigorous and hard practice of fighting arts;

- Senjo karate or Gunji karate: from Senjo (the battlefield) or from Gunji-teki (the military); any karate expression whose objective is to be applied in warfighting, in every combat situation, environment and weather conditions;

- Keisatsu karate: from Keisatsu (the Police); any karate application or expression where the use of force is necessary in Police/Law Enforcement operations. Usually techniques are strongly integrated with Judo and/or Ju-Jitsu techniques;

- Goshin-jitsu karate: karate applications mainly for self-defence purposes;

- Sento karate/Combat karate: from Sento (combat/battle), applications of karate aimed at the development of a “real and full-contact” combat fighting without making distinctions between styles of provenance (freestyle real combat). Combat karate should not be confused with “Karate Combat”, a brand/organization (just one among many others) which promotes professional full-contact freestyle karate tournements and competitions;

- Jissen karate/Kakuto karate: expressions of sporting full-contact karate sometimes practised with protections. Some schools also provide for the use of body armour and helmet with face-shield (Bogu-karate).

The fact of categorizing karate using those aforementioned “types by purposes” could appear as a purely academic and useless exercise, but it isn’t. So, to the representation of karate as a diamond with many facets, it can now be added the representation of karate as the peak of a mountain that can be reached via many different paths (schools, styles or types) that climb towards the top only to converge at the peak (the essence). Leaving aside possible “combat constraints”, which may distort for many reasons the conduct of the fighting, it is impossible not to observe lots of techniques, and their implementation, really very different from those ones considered by purists as “the only correct ones”. The basic rules that establish how a technique should be performed always have a theoretical basis as well as experience, but sometimes an “enrichment” from other combat disciplines requires a certain indulgence in favour of a further effectiveness and, more generally, for an improvement in one's own fighting style. No matter what discipline you are following or what style you are practicing, the important thing is to be able to fight, that is to be an effective fighter. It is important to consider that, with this mental approach, karate always remains a very concrete combat discipline and can also be perfectly integrated into a broader context of a generic “Combat System”, as in the case for military combat systems. Anyway, it is difficult to answer the question of how many styles of karate there currently are, apart from the most famous or most popular. All this birth and development of styles is part of an ancient, and little-known, concept of “one's own growth in the martial art” that goes by the name of “Shuhari”: Shu means “learning and following (the art)” that is following and mimicking the techniques and learning the concepts taught by the master; Ha means “trascending (the art)” that is learning and understanding deeply the nature of the techniques (how, where and when they work) and the true nature and mindset of the art; Ri means “to break away” (from the teachings to continue independently) that is to have the knowledge and skills that enable one to have one's own concept and interpretation of the art adapting the techniques in accordance with one's own body type and one's own physical capability. Shuhari is considered a natural process of personal improvement, both physical and mental, which allows one to achieve new knowledge through a personal development of techniques without ever forgetting the solid teachings of old tradition. In the end without wonder if there has been this great proliferation of styles and schools: it is the expansion of karate. Someone has found a new path to reach the peak of the mountain while someone else has added a facet to the diamond.

By Sensei Bandioli WKKO Italia

Generally speaking, everyone who has studied and practiced (or has been studying and practicing) a fighting discipline has clearly in his/her mind that any kind of discipline has its own culture, historical background, ethical rules, concepts and technical expertize and knowledge. However from ancient times till now all round the world, and expecially taking into consideration the East and the West, the approaches to fighting disciplines are very different, particularly such as in Japan. Japanese culture consists of many aspects under rigorous codes as abiding by severe rules of behavior or following strictly procedures - just think of Chado (tea ceremony), Shodo (art of calligraphy), Ikebana (art of flowers arrangements), Origami (art of folding paper), Bonsai (art of growing miniature trees), Karesansui (art of making and raking a Zen garden) and, the last but not the least, the Japanese martial arts (Karate-do, Kobudo, Judo, Aikido, Kendo, Kyudo, Iaido…). The martial arts, as any kind of art or discipline, have their own pillars rooted in tradition with their own doctrine, techniques, terminology, behaviours, rites and rituals, but, contextually, are subject to continuing enrichments, developments, individual interpretations and, sometimes, few changes… that is to say, an “evolution” over time. Karate, for exemple, had its origin in the Island of Okinawa (with just four schools and relative styles), and subsequently, after the acquisition of Okinawa and its arcipelago by Japan (1879), had itself undergone great development through the creation and development of furher styles reaching the number, more or less, of about twenty of them. After the end of the Second World War, due to a japanese political will, karate spread all over the world thanks to a great transfer overseas of japanese karate masters adding, over the years, more and more styles, some of them too much “Westernized” (in the opinion of many “purists”) because of the abandonment of traditions and technical dogmas of the early “Founders” of karate schools. At the moment in the world the most authoritative styles are about forty over a number of about a hundred, if not more. So how many types of karate do exist? Before addressing this issue, it is appropriate to make a few disquisitions as the Oriental people often say that karate is like a diamond: the core is unique but it has many facets all around. There are a few approaches, both historical and technical, that allow us to correctly frame the continuation of further considerations. There are various initial approaches that allow karate to be categorised in different ways, but mainly in accordance with: martial aims and purposes (Bugei, Budo and Kakugi concepts), ancient origins (Shorin and Shorei currents), ancient technical roots (Okinawan karate and Japanese karate schools and styles) and technical training and fighting rules (Traditional Karate and Modern Karate). As it is well known, each of the topics mentioned have an encyclopaedic dimension and summarising them in a few lines is not an easy task and a pragmatic approach is mandatory, even if it might sound superficial. Moreover, some of the topics which now are being considered are very argued topics and source of great debates and heated discussion among historians, scholars and pratictioners of all levels.

Bugei, Budo and Kakugi concepts. This is the approach by which a martial art is considered in accordance to the aims and purposes to be pursued: Bugei represents the practice of a martial art to achieve offensive skills and lethal capabilities for warfighting, that is to develop a combat discipline for the battlefield; Budo represents the practice of a martial art to achieve, as far as possible, the perfection of the balance of oneself through a rigorous discipline, hard training and physical conditioning, in order to became a better and strong human being; and Kakugi represents a far more recent concept that is the practice of a martial art solely and exclusively for sporting purposes.

Shorin and Shorei currents. These two ancient currents represent probably the origin of two main types of chinese fighting school, a synthesis of many other forms of fighting, which arrived in the Island of Okinawa and contributed to the creation of two different ways to teach (schools/styles) and practice karate: the Shorin-Ryu, from which arose all those karate styles that privilege agility and speed, and the Shorei-Ryu, from which arose all those karate styles that privilege muscular power and physical strenght. Indeed any karate style actually represent a harmonic fusion of all those features as agility, speed, balance, power, strength…and much more!

Okinawan karate and Japanese karate. Even though the Island of Okinawa (and its archipelago) has been Japanese for more than a century, there still remain many differences between Okinawan karate and Japanese karate. All those differences, that strongly affect descendant schools and styles, concern almost all aspects of karate: body conditioning exercises, traditional “basics” (kihon), body movements, training and “traditional forms” (kata), types of breathing, development of power, fighting techniques (kumite), terminology and combat tactics.